What causes regurgitation?

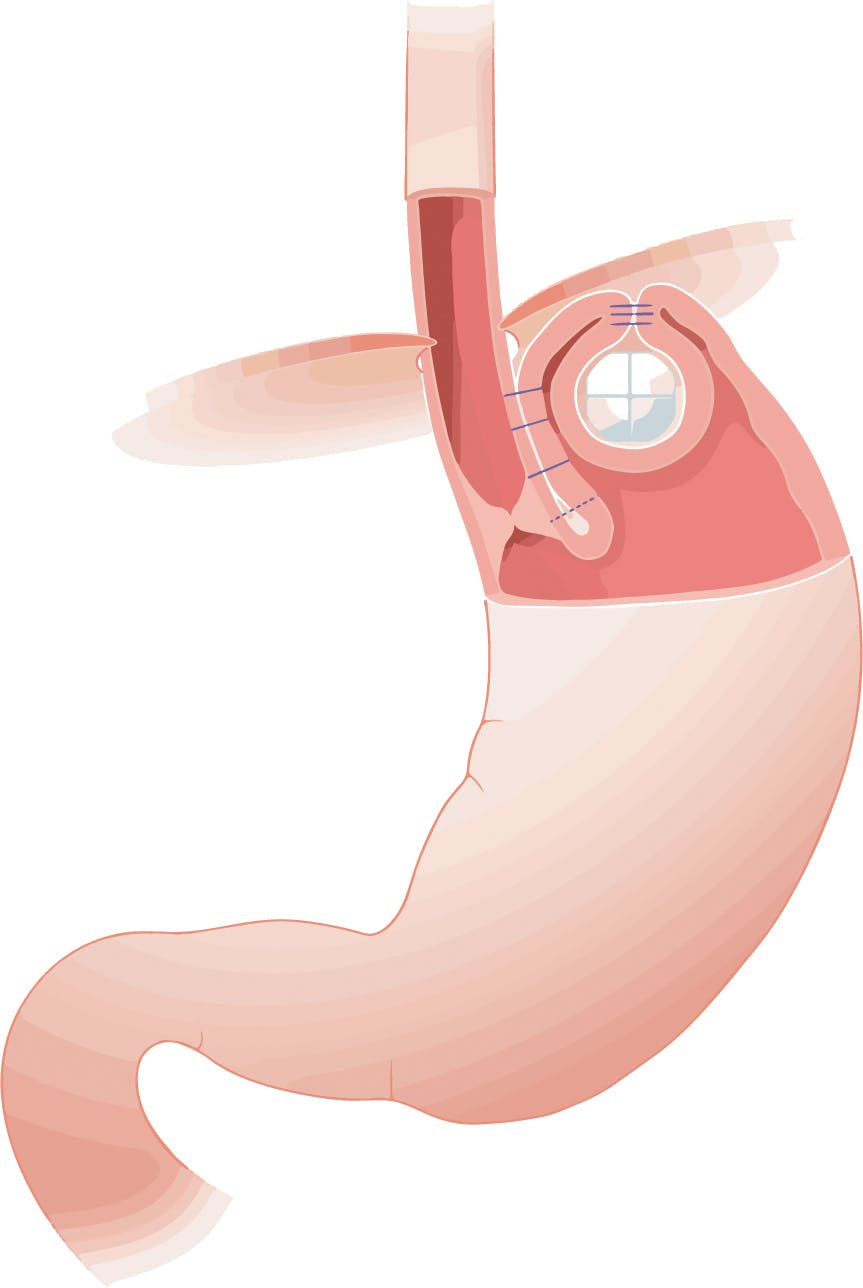

The valve at the bottom of the oesophagus (Lower Oesophageal Sphincter, LOS) ensures that acid and other substances in the stomach do not reflux up into the oesophagus. In GERD this valve fails, and reflux of these substances especially acid will irritate the oesophagus causing heartburn and other reflux symptoms. With worsening reflux, patients often experience regurgitation which reflects more severe mechanical LOS failure. This frequently occurs in the presence of a hiatus hernia which contributes to LOS weakness and is sometimes called “volume” reflux. Often patients with hiatus hernias will experience worsening of their symptoms at night when lying flat as gravity no longer helps to keep stomach contents where it belongs. Similarly bending or physical exercise can cause regurgitation.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth can also cause regurgitation particularly after eating and sometimes at night.

There are some other regurgitation causes which should be excluded. These include;

- Achalasia

- Rumination

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Pregnancy

- Overeating

How is regurgitation diagnosed?

The cause of regurgitation is diagnosed by a combination of a clinician listening to a patient’s “history”, physical examination and then diagnostic tests.

Diagnostic tests include;

- Gastroscopy: Otherwise known as upper GI endoscopy this involves inserting an endoscope through the mouth or nose into the oesophagus and then through the stomach and duodenum (together known as the “foregut”). The endoscope has a high-definition camera enabling the operator to look for structural abnormalities such as hiatus hernias. They will also evaluate the lining of the foregut, for instance identifying oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus and ulcers. If necessary, samples of tissue (biopsies) can be taken for analysis. The examination can be performed with local anaesthetic spray, intra-venous sedation or under general anaesthetic.

- 24-hour catheter reflux monitoring. A small tube (catheter) is inserted through the nose to the bottom of the oesophagus and measures reflux events usually over 24 hours at the bottom as well as the top of the oesophagus. It will also include a pH sensor in the stomach to ensure normal acid production. The catheter is attached to a recorder about the size of a mobile phone and patients can record when they experience symptoms allowing correlation between the two. These are known as “symptom associations”. pH testing assesses acidic/non acidic reflux events. Modern testing includes impedance which offers the advantage that it also distinguishes between liquid, solid and gas reflux events. So, for instance, impedance can identify belching and its relationship with reflux and can accurately record regurgitation events.

- Oesophageal pH capsule reflux test. The Bravo test involves attaching a tiny capsule during a gastroscopy onto the lining of the oesophagus just above the stomach. This records acid reflux over a period of 48-96 hours. Instead of a catheter it sends the data wirelessly to a recorder and falls off after the test is complete. The procedure is usually performed under conscious sedation.

- Barium swallow. Sometimes useful information can be obtained by performing x-rays during which liquid barium is swallowed. The images produced can help to diagnose reflux, achalasia and structural abnormalities such as hiatus hernias and tumours.

- High resolution oesophageal Manometry (HRM). In diseases of the oesophagus including GORD (Gastro Oesophageal Reflux Disease), the normal function of the oesophagus can fail. Since regurgitation can also be caused by conditions in which the LOS fails to relax (Achalasia) and behavioural abnormalities including rumination HRM is often recommended. This will very accurately measure pressures along the length of the oesophagus and how the nerves and muscles that coordinate swallowing are working as well recording the function of both upper and lower oesophageal sphincters. A small flexible tube called a catheter is passed through the nostril and down into the oesophagus. The tube has tiny sensors which measure the pressure exerted by the muscles in the wall of the oesophagus. The patient will demonstrate swallowing food and drinking liquid, whilst the tube relays the information to a computer.

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) breath test. This is a simple test usually performed at home in which a sugary liquid made with either glucose or lactulose is first drunk. Over the next two hours samples of breath are then taken by breathing into small bottles. These are then returned to the laboratory where the concentration of hydrogen and methane gases are measured. These gases are not produced by human cells but are released from micro-organisms in the gut during their metabolism of carbohydrates including glucose and lactulose. The pattern of their concentration in the samples taken during the test can be diagnostic of abnormal SIBO and Intestinal Methanogenic Overgrowth (IMO).

What are the treatments for regurgitation?

Reaching the right diagnosis is key to planning treatment. Having excluded other causes the treatment of regurgitation caused by GERD an escalating strategy depending on effectiveness is usually recommended. Of note, regurgitation usually reflects relatively severe reflux. Even powerful anti-acid medications such as PPIs frequently don’t work. The mechanical cause of the problem makes it particularly well suited to surgery.

Lifestyle changes;

- Dietary changes such as eating smaller meals, avoiding trigger foods, eating earlier in the day

- Losing weight

- Stopping smoking

- Elevating the head of the bed at night

Medications;

- Alginates such as Gaviscon

- Simple anti-acids such as sodium bicarbonate

- H2 blockers such as Famotidine and Nizatadine

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as Omeprazole and Nexium

- Others including Baclofen

Anti-reflux procedures;

- TIF

- Laparoscopic fundoplication

- Laparoscopic LINX

- Laparoscopic RefluxStop

- C-Tif